We are going to France. How did this happen? Even landsharks make me nervous. So, how did it happen? Like this.

Several years ago I began the search for my father’s family. I knew that five generations had lived in Louisiana, but I knew little of the French connection until I found a Denis Chalaire listed in Paris prison records dated 1790–surely the worst of times to be in a Paris prison. Was he a common thief, or a victim of the “deluge”? I still don’t know. The next time I searched, the document had disappeared, and I put the search aside for several years. The first Chalaire in Louisiana appears to have been Jean François, born 1676 in Ile de France; he appeared on Louisiana tax rolls at about the time of the Revolution. Denis may have gone to Canada or Switzerland, but he did not immigrate to Louisiana. (I will return later to the subject of prison records during the French Revolution.)

About a year ago, I “reopened” the search and have been poring over the many sources now available online, including historical documents. The first solid clue was a journal/log, recording the administrative activities of a dauphin of France–the future Louis XI, aka Louis the Prudent, and, more ominously, the Spider King. I was initially confused by the log entry titles. All entries began with a date and a locale, many of them titled “Chalaire,” with dates beginning in 1454. Why was “Chalaire” a place, not a family? I found the answer on a present day tourist site that refers to the Maison Forte de Chalaire as one of the attractions in Mours St-Eusèbe, a small town in the Rhône-Alps.The journal recorded the dauphin’s edicts for the governance of the Dauphiné, a region in southeastern France, and the “Chalaire” entries were recorded during his stays at the Maison Forte de Chalaire in Mours Saint-Eusèbe. Apparently, it was a favorite spot of his–he visited often.

The seigneur de Chalaire had relinquished ownership of the house long before the royal visits. Records from the Collègiale of Saint-Bernard in Romans-sur-Isère have become central to the search. No Chalaires were at home to receive the dauphin, because Pierre Colerio (Chalaire) had long ago–in 1063–made a bequest to the Church on behalf of his deceased wife; it included the “farmhouse” (the maison forte?) and some land.

The original entry is in Latin and refers to the house, land, and “castello de cabrerii” as being in the center of the Villa Arratica. I have found two translations of the register entries, both from Latin to French One translation refers to the “castello de Cabreriis en villa de Colerio” (Giraud). Was villa Arratica renamed villa Colerio? The original Latin entry is short but it raises questions: Colerio/Chalaire? Is Chalaire derived from Colerio? Did the clerk spell the name correctly? Villa Arratica? Where was villa Arratica/Colerio? Most searches point me to Arras-sur-Rhone, which is in the wrong area. And what is the significance of “castello de cabrerii? I thought it might mean stable for horses, but, if so, why didn’t the French translator refer to “écurie”? And finally, why has the name of a long-gone-lord-of-the-manor remained attached to a place for almost a thousand years? Is that common practice in France? We also have a street in Mours (Rue de Chalaire) and some very fine lakes in nearby Peyrins (Étangs de Chalaire). Perhaps it has something to do with the nature of fiefs or Salic law.

Maison Forte de Chalaire 1

I knew I wanted to find “our people,” phobias notwithstanding, so I began to look for places to stay, “our” maison forte being unavailable. Forgetting for the momemt my fear of cold-eyed, sharp-toothed creatures waiting for me to tumble from the sky into the inky depths, I told my brothers about my search. They were enthused, and now my fear is trumped by non-refundable tickets.

I spent 10 years as owner/operator of a restaurant and bed and breakfast. I love old buildings, old houses, but I never stay in B&Bs. This is different: if you’re off to find your roots and your castle, something redecorated in modern monastic isn’t quite comme il faut. What I found was another maison forte, the Maison Forte de Clérivaux (www.clerivaux.fr) in Chatillon-Saint-Jean, a few miles from our maison forte. I am as excited about staying at Clérivaux as I am about searching for traces of our family–almost.

What exactly is a maison forte? A brief definition is “fortified manor house,” but the following page from Wikipedia, gives a fuller description :

It is from the last third of the twelfth century that the texts report qualified buildings “domus fortis, domus fortalitis cum, cum tota forteresia domus, domus cum poypia, fortalicium domus and turris fortis.” It is the appearance of fortified houses or house fortified . These buildings, which are not castles ( castrum or castellum ), are more than just a residence (domus). This phenomenon will continue largely in the first half of the thirteenth century and ending in the early sixteenth century . They may have the appearance of a solid house with tours or have the appearance of a building constructed of odds and ends. They are often located on the outskirts of towns along main roads or at the border of a large manor . They belong either to juniors, relatives or allies of large noble families or to become rich bourgeois and exercising important offices. The fortification of a house, that is to say, the addition of towers, fences, ditches, slots, assumed special permission from the dominant lord and all the neighboring lords of the parish. (Wikipedia)

Looking for Pierre

Variations in surnames are apparently typical: Chalaire, Chaleyre, Chalere, and Cheylard are all found in the same region, but I have not yet found Colerio mentioned anywhere. Where is villa Arratica? Colerio sounds Italian: Did Pierre return to Italy? Switzerland? Perhaps I will find traces of Pierre Colerio/Chalaire in the Ardèche–there is a “hamlet” named Chalaye in Saint-Agrève in the Ardèche, as well as a village named “Cheylard.” Surnames were a new thing at that time and the same person might write Challaye on one document, Challayer on another, or Chalaye on another. The best way to find Pierre may be to follow the fief.

The maps that show the fief are almost as varied as the surnames. One map of the Dauphiné (therefore, prior to 1349) shows “fief de Chalaire,” another indicates “fief de Chaleyre,” both of which are near Peyrins–also where the lakes are located; however, a third map shows the” fief de Chalere” in the Ardèche, NW of Peyrins,” and “fief de Cheylard” near Peyrins. Do all of these maps describe the same fief? Is “villa Arratica/Colerio” part of the answer? I’m glad Romans sur Isere has extensive records and that it’s only a few miles from Clérivaux. Others places to check are Vienne and Valence, and possibly Tournon-sur-Rhône, which is in the Ardèche. Perhaps Pierre, using a variant of Colerio/Chalaire, left Peyrins and settled in the Ardeche after his wife died.

Poor us–somehow squeezing research between visits to Roman ruins and lovely medieval villages, while enjoying French bread, cheese, and wine.

19 August

Name variations are complicating this search, but there are a number of sites/documents dedicated to untangling the threads. For example, jeantosti.com.

Chalaye: The name is often found in the Ardèche (variants: Challaye, Chalaya, and certainly Chalay). The toponomy designates a region of a particular type of fern. There is a hamlet called Chalayes in St-Agrève. Other forms: Chalayac, Chalayer (in depts. 42 Loire, 26 Drome, 07 Ardeche).

Another valuable source is an ebook: Dictionaire Topographique du Departement de la Drome: Comprenant les Noms. Ed. Justin Brun-Durand. The names, years, and info in parens are all important :

Chalaire, h. et ch. c__ de Mours–Villa de Colerio, Colerum, 1075 (Cart. de Romans, 287 )–Chalarium XII siécle (ibid 330 ) –Chalayre 1405 (terr. de Saint-Bernard) –Chalero 1449 (terr. de Vernaison) — Apud Chalarii 1450 (Numismatique de Dauphiné, 372) — La Maison Forte de Challeyre, Challarium, 1514 (arch. de la Drôme, E1855) –Chalere (Cassini).

Ancien fief de la terre de Peyrins, appartenant en 1450 aux Dauphiné, Chalaire fut ensuite acquis par les Rochelle, qui s’eteignirent vers 1515 chez les Vallin. En 1672, ces derniers étaint seigneurs de Chalaire, conjoinment avec les Falcoz de la Blache. (61) [The first section is a list of references and dates showing the name changes through the centuries. The second part says that Chalaire was an old fief in the land/region of Peyrins, belonging in 1450 to the Dauphiné. It was later acquired by the family Rochelle, which merged with the house of Vallin in about 1515. In 1672, the last lords of Chalaire merged with the Falcoz de la Blache]

20 August

Pierre Colerio (Chalaire) had given the house and some land to the church in 1063. How did Louis get it back? Or did the church receive the revenue, not the land. I think the land must have reverted to the crown when Humbert II sold the Dauphiné to Philippe VI in 1349. One of Louis’ edicts (15th cent) appointed Jean Arthoud as châtelain of Chalaire. Brun-Durand (above) says the first seigneur was Rochelle, but a third source says that Arthoud was the “first seigneur” (14th century), that it then passed to the Vallins family (15th century), and to Joachim de Falcoz (17th century). It was then given to the Ursulines. In 1791, it was divided into lots and sold to 9 buyers; in 1850 it was sold to the city.

Following Brun-Durand (above) may be the best way to follow the evolution of the name and perhaps the descendants of Pierre: Colerio, Colerum, 11th century; Chalarium, 12th; Chalayre and Chalero, 15th; Challeyre, 16th; Chalere (Cassini), undated. But I also want to find out what happened to the remainder of the fief, because the part that Louis granted to Jean Arthoud, et al, was not the entire amount that Pierre owned. On second thought, maybe it was. I need to reread the original register entry–if I can find it again. I have new insight into the downside of online research.

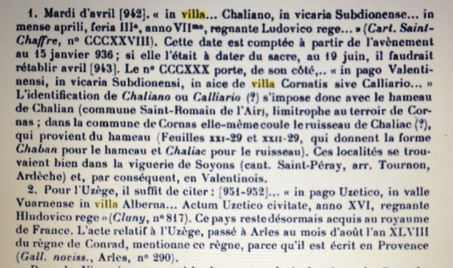

I finally found a reference to villas Colerio and Arratica, but the date is 10th century:

Will need help with the Latin, but I think Manteyer is discussing references to Chaliano or Calliario and trying to tie the names to a neighboring hamlet Chalian (in the “commune of St-Romain de l’Air? , which borders the land of Cornas–where Chaliac brook or stream runs). He includes question marks to indicate the confusion of name variations, I think. Manteyer’s link between Chaliano and Calliario is closest I’ve found to Colerio/Chalaire and etc. Jeantosti.com lists “Chalayac” as one of the forms of Chalaye (along with Chalayer), and Manteyer lists Chaliac as the stream near the hamlet of Chaban. Where is Chaban?

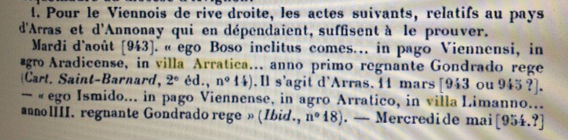

Other than the St-Bernard note, placing the bequest “in the center of villa Arratica,” Manteyer’s book is the only reference to villa Arratica I’ve been able to find. Saint-Bernard’s was founded in 838, and Manteyer’s note indicates that villa Arratica existed in 943; since the bequest was made in 1063, Manteyer’s note provides some continuity, suggesting that villa Arratica could be connected to our Colerio, descended from Chaliano or Calliario mentioned in the note. I was beginning to wonder if the clerk had gotten into the brandy before entering Pierre’s 1063 bequest. The note below, also from the Manteyer text, mentions Annonay, which leads back to the Ardèche.

Among the early inhabitants of the Dauphiné were the Visigoths and the Burgundians; power was shared between several powerful lords and arch/bishops in the church. In the 10th century, Boson of Provence, then governor of Vienne, named himself King of Burgundy, and the region became known as the Kingdom of Arelat, which remained independent until 1032 (Manteyer cites a reference to “Boso” (below), who is perhaps “Boson of Provence”?) Guigues I, Count of Albon, took control of the region; he died in 1070, which puts him within Pierre’s lifetime. There were frequent turf wars between the rulers of Dauphiné and the Savoy. Pierre may have received the fiefdom from one of the Counts of Albon, from Guigues I to IV; or he may have been one of the Savoyard barons who fought against Guigues. The Haute-Savoie is often listed as one of the places where the name Chalaire is found. At least we can confirm that villa Colerio/Arratica was in the Dauphiné region.

Also found a Tedbaldus de Chalere mentioned in a document dated 1100, with references to Stephen–as in Mathilde and Stephen! Tedbaldus is also listed in the Domesday Book (surely there couldn’t be two Teds); and something called the Calendar of Charters Rolls that lists everyone granted a charter by Henry III (England) includes a “Chalere” (Sir H.C. Maxwell Lyte, 1972). That’s exciting–Henry III was Edward I’s father. I cannot believe this. I hope Chalere was one of the Barons that later joined Simon de Montfort against Henry and Edward I (Longshanks in Braveheart). But maybe Chalere of the Charter exercised the better part of valor and moved on to France before the Battle of Evesham.

I just realized that Tedbaldus is 12th century, de Montfort is 13th, and Pierre is 11th. I’m moving in the wrong direction! I want to find out how Pierre acquired the fief and what land was included in that fief. I want to know what happened to Pierre after the date of the bequest, and I want to know when and where he died.

Another reference that appeared once on a search and then disappeared was to Gerard/Gerald de Chalaire in the XI or XII century. Not making that up. It was in a 2010 Univ. of California digitalized copy of the journal Societe d’archelolgie et de statastique de la Drome, Valence (1971, Issue 382, p. 253), but that version stopped appearing in searches. Might have to look for that issue in Valence or Romans.The journal refers to a 12th century charter given to Gerard or Gerald Chalaire. I’m anxious to know how this ties to Pierre–if it does.

22 August

looking for good sites:

http://www.valdedrome.com/assets/files/decouverte/villagesperches/livret-village-perches-ANGL.pdf

http://www.adsummus.com/scratchpad/RCCVB/mont-interest.html